Dušan KOS

THE VRHNIKA JUDGE’S WOMAN

Portrait of an inappropriate love affair in the early bourgeois era

The article deals with the phenomenon of relationships and the forms of love in the late 18th and early 19th century in Slovenian territory between people of different social background and age who had no noble rank. At its focus is an analysis of the relationship between the Vrhnika market town judge Janez Nepomuk Jurkovič and his three-decades-younger protégé and foster daughter Uršula Cerer between 1799-1803. Jurkovič found his pregnant mistress an apartment in Ljubljana, where she had to defend herself because of suspected prostitution before the mayor of Ljubljana in 1801 and 1803. However, Uršula’s life differed from that of morally downfallen women because she had a home and support for herself and the child; at the same time, it differed from the lives of others involved in concubinage and brief adulteries. More is known about Uršula’s and Jurkovič’s actions and emotions than about other similar relationships because five letters that Jurkovič sent between 1802-1803 to the otherwise illiterate Uršula have survived. Their content and the minutes of the hearings reveal not only the technicalities of the love affair but also their care for the child and a typical biedermeier love that was completely unlike the late baroque one.

Daša LIČEN

AMID EMPIRE, NATION AND NOSTALGIC VISION

Erecting and removing monuments in Hapsburg Trieste

The article aims to shed light on the past and present of monuments that were erected in Trieste after the 16th century as expressions of loyalty to the Hapsburg dynasty and the Austrian state. I consider monuments artefacts of memory. The reasons behind their construction were conditioned historically by specific social and political circumstances. The same applies to their reception once they were erected. With the spread of national movements from the mid-19th century, Hapsburg monuments received new connotations and became objects of various, even contradictory ideological interpretations. Many monuments were removed for this reason; however, with a recent onset of Hapsburg Monarchy nostalgia, they have made a comeback in the Trieste public space.

Damir GLOBOČNIK

THE SLOVENIAN MONUMENT SCANDAL IN CLEVELAND

The monuments to Ivan Cankar, Friderik Irenej Baraga and Simon Gregorčič in the Yugoslav Cultural Garden

In 1930, the City of Cleveland granted some ethnic communities the right to use parts of Rockefeller Park at their own discretion. Slovenians decided that the Yugoslav Cultural Garden would become the location for a monument dedicated to the writer Ivan Cankar. At the beginning of 1933, the City of Ljubljana donated a cast of the Cankar monument, the work of sculptor Peter Loboda (1894–1952). Collecting voluntary contributions for raising a monument to Cankar did not go well. In september 1935, they raised a monument dedicated to Bishop Friderik Irenej Baraga. Just before unveiling the Cankar monument and the monument to Simon Gregorčič, they found that Cankar’s monument had been stolen from the city storehouse. The Catholic camp placed blame for the stolen monument on the socialists, who had endeavored to place the Cankar monument in the Slovenian National Hall. The Yugoslav Cultural Garden board commissioned a new statue of Ivan Cankar, which would be based on photographs of Loboda’s monument, and executed by Rudolf A. Mafka, a Cleveland sculptor of Slovenian descent. The Cankar monument was unveiled on 25th July 1937.

Miran APLINC

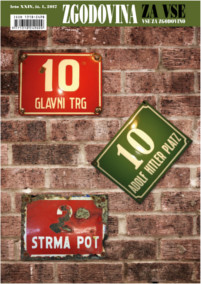

“EVERY STREET, SQUARE AND ROAD, EVEN IF IT ONLY HAS ONE HOUSE, NEEDS ITS OWN NAME”

From house numbers to naming streets and squares in Šoštanj

The article deals with the naming of Šoštanj streets, from the first enumeration and the first naming in 1931, through the re-naming during the occupation, re-re-naming in 1953 and the changes up to the present. Šoštanj had been the economic and administrative center of the valley of Šaleška dolina since the second half of the 19th century. After it was officially granted city rights in 1911, the conditions for naming the streets and squares were met; however, the process did not begin immediately. The first naming of streets and squares took place in 1931 as the result of growth and urbanization, which later slowed in pace because of the growth of nearby Velenje. The decline stopped only a few years ago. In the past, the streets of Šoštanj were named after important people from Slovenian, Yugoslav and cultural history. after the end of World War II, some streets were named after the fallen fighters of the partisan movement, revolutionaries, communists and national heroes. For clarity, all names are presented in chronological order.